- Home

- Yaron Reshef

Out of the Shoebox Page 2

Out of the Shoebox Read online

Page 2

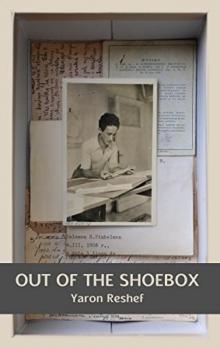

Asher Meiselman, Ilana, my mother, and my father Haifa, 1940

My mother said, in her memoirs:

“… Even before his return to Chortkow to marry me, my husband opened an office in Palestine with a partner. My husband was an architect while the partner, named Wolf, was an engineer. They had plenty of work, because Hadar Hacarmel neighborhood was being built at the time. There was a shortage of housing in Haifa back then…

We bought an apartment under construction on Hillel street in Haifa. It was a 2 bedroom apartment, one room of which was always rented out, because no one at the time enjoyed the luxury of two rooms. We all lived modestly in those days. Until the building was complete, we lived at Uncle Herman’s on Nordau street. That was a very difficult period for me, because Herman’s wife, Heidi, was used to having maids and couldn’t cook at all, while Herman loved such Jewish-Polish dishes as gefilte fish, stuffed cabbage, etc. So I was their unpaid cook (even though my family used to have a cook too, I had taken an interest and learned to cook.) Aunt Heidi started learning Hebrew, which she had been totally unfamiliar with. She spoke many languages: German, French, English; and decided to learn Hebrew. When half a year had gone by without her managing to grasp any Hebrew, she gave up, deciding it simply wasn't for her…”

According to my mother’s memoirs, my parents’ first apartment upon arriving in Palestine in 1934 was 6 Nordau St. I know that place well, having spent much time there in my childhood. The building was designed and built by my father for relatives who came from Austria. With its Bauhaus design, the building stood out. Most of the raw materials and interior finishes were imported from Europe, and the apartments were rented out on a monthly basis or for key-money, constituting a source of income for my relatives, who kept the property till their dying day. I therefore knew that during 1934 they lived at 6 Nordau, then moved to Hillel St., house number unknown. Father, who worked as an architect at the time with an engineer named Wolf, rented an office at 4 Achad Ha’am St. Later, my parents moved to that place, where my sister was born and where I was born in 1951. But as far as I know, they moved there only in 1937.

Having reached a dead end, I decided to try and contact Hanni Amor at the Custodian General’s office, figuring that, at worst, she’d refuse to advise me on how to proceed. I explained that according to my mother’s memoirs my parents lived first at 6 Nordau and then on Hillel St., number unknown. Hanni confirmed that the street where my father lived when purchasing the land was indeed Hillel rather than Nordau, but stressed that I need to provide the house number and some legal proof that the person who had lived there was indeed my father. She further repeated the requirement to prove the connection between my father and one Mordechai Liebman.

How on earth was I to find that elusive house number? Days went by, and no creative idea came to me. True, the task now boiled down to locating one certain building on one street, but said street had some seventy-five houses. I was at a loss. Based on my mother’s memoirs, the move to Hillel St. occurred after a short period on Nordau. I knew that the house on Hillel was probably built in 1934, so that my parents must have moved in either late 1934 or early 1935. I had one more early memory, in which my mother described to me the switch from the comfortable life in Chortkow to the modest living in Palestine. She’d say: “At first I was a cook at Herman and Heidi’s place, then we moved to Mayer Fellmann's place that was very small, and we always rented out a room to another lodger, and there was no privacy… everyone lived very modestly.” This was my mother’s way of saying that they lived in deprivation. Did my parents buy the apartment from this Mayer Fellmann? Was he the owner, or the contractor who built it? At the time, in the early 1930s, most housing in Hadar Hacarmel was built for home owners who also owned the land. These people financed the construction of the building, usually lived in one of the apartments and sold or rented out the rest. Mayer Fellmann may have been the proprietor from whom my parents bought their home on Hillel St. I decided that, if push came to shove, I’d scour City Hall archives for the building permits for all buildings on Hillel St., until I found one in the name of Mayer Fellmann. I knew the city’s archives were computerized, which would make the task easier, but thought that, since I couldn’t trust my memory regarding the landlord’s exact name, I should postpone this hunt, which took on Sisyphean proportions.

Another possibility was that my parents had bought an apartment in one of the buildings designed by my father, who had designed several apartment buildings in Haifa, including the one at 6 Nordau, and another at 7 Bar Giora St. I began by looking into the ownership of the house on Bar Giora, in the hope that this would reveal the same landlord for both buildings, thus leading to the sought-after address of the flat on Hillel St. Imagine my disappointment when a search of the computerized city archives showed that my father's design, from early March 1936, was for a woman named Sara Chana Preminger – no connection to Mayer Fellmann nor to the address of a house on Hillel St.

I’d found out about the house at 7 Bar Giora St. thanks to an architecture student named Uri Zirlin, who’d studied at the Technion over fifteen years ago. Zirlin called my sister one day to ask if she was the daughter of Shlomo Zvi Finkelman, who was a Haifa architect in the first half of the 20th century. He recounted how, while writing a seminar paper for a course given by architect Silvina Sosnovsky and historian-cum-Israeli-architecture-researcher Prof Gilbert Herbert, he had to research a certain unnamed architect who’d designed a building on Geula St. in Haifa. The building assigned to Zirlin appeared in a study, commissioned by Haifa municipality, of conservation-worthy buildings. Zirlin was to locate information about the building's architect and try to find additional buildings designed by him in order to create a portfolio that would ultimately be part of the archives of the Technion’s Department of Architecture. I thought that if I found this student’s paper, I’d find additional facts about my father and other buildings he designed and built, and perhaps even hit on my objective, i.e. his places of residence in the ‘30s. I pondered the strange coincidence that Prof Herbert, my professor at Bezalel, gave a Technion student the assignment of researching architect Shlomo Zvi Finkelman and his contribution to architecture in Haifa, unaware that that the latter was my father.

Ilana prepared and sent Zirlin a summary of my father’s biography that included: family background, architecture and engineering studies at Baugenwerbe Schule in Vienna, Austria; how he came to Palestine to study architecture at the Technion; info about several buildings he designed; how he worked as an architect for the British Mandate for two years during WWII; and later for the Israeli Ministry of Trade and Industry in Israel, when he worked on the planning and building of the Artists’ Colony in Safed. Zirlin promised to send my sister a copy of his seminar paper, but failed to keep his promise.

I decided to try and find out whether Uri Zirlin’s seminar paper was on record at the Technion, so that I could see what information about my father it contained. I knew that seminar papers were submitted during the fourth year of studies, so assuming the student had completed his studies, he might be working as an architect today. The next step was searching the Internet for “Uri Zirlin”. There were several people by that name in Haifa, but none seemed to have any connection to architecture. Still, I thought it worthwhile to call four persons by that name living in the Haifa area. The first three proved to be irrelevant – “wrong number”, “don’t know any Uri Zirlin”, but the fourth did indeed answer to that name. When asked if he by any chance knew an architect who’d studied at the Technion, he wanted to know why I was asking. I explained that I was looking for a person who’d written a paper about my father, and he replied that, though he’d studied architecture and worked at it for a while, he dropped this occupation. Moreover, he claimed he’d never heard of my father and never wrote a seminar paper about architectural conservation in Haifa. I detected a kind of evasiveness in his voice, so I apologized for the intrusion and hung up.

About architect Silvina Sosnovsky,

on the other hand, I found plenty of material. Apparently she was very active as an architecture researcher in Haifa, who focused on the location and conservation of buildings built in the 1920s-1940s. When trying to find her via the Technion, I learned that she’d retired; and after explaining my reason for seeking her out, they agreed to give me her number so I could contact her directly. Ms Sosnovsky graciously listened, took down my father’s details and suggested I call her back a few days later. I waited in suspense for a week before calling again. “I remember your father’s name,” she said, “and I’m familiar with the buildings on Nordau and Bar Giora streets that you mentioned… they are indeed in a study of conservation-worthy buildings that I conducted for the City of Haifa in 2001… but I can’t find any other material related to him… Nor can I find any mention of your father in my other published work… I’d advise you to apply to the Technion’s Architectural Heritage Research Center… Maybe there’s documentation of your father’s work there, as well as copies of papers written by students whom I supervised.”

What a let-down. I expected to garner some sort of new information, or a clue at the very least. But my high hopes were dashed. The very next day I tried to contact the Research Center, but though I found information on its activities on the Internet, it took a whole week of persistent attempts until I finally got through to them on the phone. The woman at the other end of the line, Hedva, listened patiently to my story, took down some notes, asked me to email her a few more details about my father, and said she’d search the archives, warning me that it would take time. “However,” she added, “if there is information about your father, it will turn up.” Two weeks later, after intensive searching, nothing turned up. Apparently there was nothing about him in the archives.

As I was dialing Hedva’s number to thank her for her efforts, it occurred to me that I hadn’t mentioned that my father had been a Technion student for about two years before embarking on an architect’s career in Haifa. “Then why don’t you try to find out whether your father’s student file still exists in the archives,” Hedva suggested when I told her. Does the fact that my father was a student there change anything in the way her search was conducted? I wondered; it had never occurred to me. I did not for one minute expect his student file to still be there, after seventy eight years. But, figuring I had nothing to lose, I proceeded that very day to call the office of the Technion’s graduate program in architecture to ask if there’s any chance of finding any record or information relating to my father. I spoke to Ms Ada Sales, graduate studies coordinator. “Look,” she said, “there’s not much chance that we’ll find anything relevant, so don’t expect too much. Many files were damaged over time. But if it’s there, it will be found.” She asked me to send her a copy of a will or any other document proving that I’m my father’s beneficiary, to ensure I had the right to any information, should it be found.

I immediately wrote to Ada:

“Dear Ada, thank you for your time and your willingness to help. I am seeking information related to my father’s studies at the Technion’s Department of Architecture, his student registration file or any other relevant information. My father studied at the Technion in the early 1930s, between 1932-1935 I believe. His name was Salmon Hirsh Finkelman, though he Hebraicized his given names to Shlomo Zvi, and appears in some documents as Shlomo Hirsh Finkelman. My father died in 1958 when I was seven, so I don’t have much to go on. I’m particularly interested in finding out facts about the period of his life before he married and started a family. At your request, I’m attaching a copy of the probate which states the date of his death and the fact that I am his son and one of his beneficiaries. In that document, my name appears as Yaron Menachem Finkelman. I later Hebraicized my surname to Reshef. I am also attaching photos of my father’s first British ID, but I think it was issued a few years after his Technion days. My father arrived in Palestine on a student visa, without an ID. I can be reached by email or phone, see contact details below. Thank you in advance and have a good day, Yaron.”

Nine days later, while I was in the States on business, I received Ada’s reply:

“Hi, I’ve retrieved from the archives a few files that seemed to me similar to the information you supplied, and have them handy. You’re welcome to come over and peruse the material. All the best, Ada.”

I replied at record speed. I told her I was in the US for two weeks, and asked if I could call her for more details. Ada replied within minutes with a phone number, which I called immediately, very excited. It was enough for me to hear a few details about the retrieved files to realize that one of them was my father’s enrollment record. “There’s only one problem,” said Ada, “contrary to what you said, your father didn’t actually study at the Technion at all. He did apply and was accepted, but the file contains no record of actual studies.” Ada continued to explain that the enrollment file contains several letters in my father’s handwriting, and invited me to come and see the material. “Maybe we’ll be able to give you the entire file, and keep copies for us… Your father’s penmanship is beautiful and his Hebrew is excellent. His entire file is preserved in perfect condition.”

I can’t begin to describe my excitement. I’d finally found a lead connected to my father. I began imagining what might be in the file, shook up by the revelation that my father apparently did not study in the Technion at all. My time in the US stretched out infuriatingly slowly, as I counted the days till my return. Gradually it began to sink in that the Technion’s information would probably not shed any light on my father’s place of residence. If he never actually studied there, what were the chances that his student record contained his address in Palestine? On the other hand, I hoped the file would contain the address of my father and his family in Chortkow – something I lacked and would be thrilled to acquire.

As soon as I got back I called Ada and made an appointment for the following day. I didn’t know what to expect, couldn’t imagine what I’d soon see.

The trip to Haifa flew by… Ada pulled out a gray folder containing an assortment of letters and documents. I immediately recognized my father’s handwriting, with which I was familiar from old documents found at my mother’s many years earlier. His handwriting was legible and the style clear and fluent, as if written in the writer’s mother tongue. The folder contained correspondence between a young man applying to study architecture and construction and an academic institution detailing the admission requirements.

This is my father’s first letter to the Technion:

Chortkow, 8 Aug 1932

To: The Office of the Registrar, the Technion, Haifa

a) I am writing to you with a request that you send me all information relating to admission to the Technion. I myself graduated from the construction school Baugenwerbe Schule Wien in Vienna. I studied for three years (six semesters) and have practiced for three years. Therefore I would like to know which year I can be accepted into.

b) I would also like to ask you to give me information on how I can immigrate to the country. If you can send me a demand, if you have one. And what guarantee is required.

I kindly request that you reply as soon as possible, so that I can forthwith follow my desire to study in a Hebrew Technion.

With best wishes and shalom,

S. Zvi Finkelman

My address:

Salmon Hersz Finkelman

Czortkow

279 Szpitalna .nl

Polania

I could tell immediately that my father went through the motions of applying to the Technion not because he truly wanted to study there, but with the intent of emigrating to Palestine, using studies at the Technion as a means to that end. The fact that my father refers to his studies of architecture in Vienna as though it was merely secondary school seemed a way to make double-sure that he’d be accepted. Anyone who looked carefully at the diplomas my father attached could easily see that he’d attended an ordinary high school in Chortkow – referred to at the time as a gymnasi

um – then continued to study architecture in Vienna. Though my father sent the original diplomas from the Vienna institution of higher education, it seems that no one looked into them too closely, accepting my father’s statements at face value. According to my father’s letter to the Technion, he studied six years in high-school plus another three years at a high-school for architecture in Vienna – a total of nine years, which is highly unlikely.

My father was accepted into the first year. He did not dispute this decision, only urged the Technion to send him a letter of admission. The Technion sent a copy of the admission letter to the British Mandate authorities, which in turn granted my father the sought-after entrance permit to Palestine. The letters were arranged chronologically in the folder: a letter from my father followed by the Technion’s reply, and so on, as if time stood still. It was easy to see that a letter between Haifa and Chortkow took about two weeks. I must say that the Technion had been amazingly efficient in its replies, generally answering on the following day. My father, who wished to make aliya (immigrate to Israel) as soon as possible, continued urging the Technion, saying he was very eager to begin his studies in early 1933.

As strange as it may sound, I was somewhat disappointed. Though I knew by now I would not find Father’s first Haifa address in this folder, I continued to pore over the folder with Ada, reading one letter after another and joking about my father’s assertive way of pressing the Technion to speed up his acceptance. Later, when I continued to explore where Father got the idea of trying for a student visa, it turned out that Zionist activist Ze’ev Jabotinsky visited Chortkow in 1930 – the same year Father returned from Vienna and was appointed leader of Betar in his hometown, where the movement had some 150 members. In his talks, Jabotinsky used to enumerate the different ways of immigrating to Palestine, including student visas. Only in late February 1932 did Jabotinsky publish his article On Adventure, in which he called for illegal aliya to Eretz Israel. I have no doubt that my father was influenced by these ideas. Ada and I continued perusing page after page, admiring the correspondence. Once my father sent his transcripts, the Technion’s reply arrived on 28 Sept 1932, saying that my father was accepted into the program, but had to immediately send the deposit of 15 Israeli lira plus 500 mil for the visa expenses. Their letter stresses: “After the visa process which takes a few weeks, we must point out that if your trip is delayed so that you arrive here after Jan 1st, 1933 you will not be able to begin studying this school year.” It took the letter a week to reach my father, but he could not buy Israeli lira in Chortkow. He bought American dollars instead, sending the cash with the following letter:

Out of the Shoebox

Out of the Shoebox