- Home

- Yaron Reshef

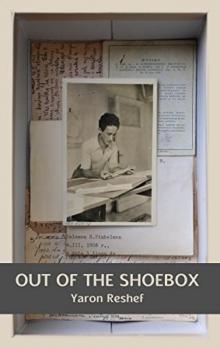

Out of the Shoebox

Out of the Shoebox Read online

Out of the Shoebox

by

Yaron Reshef

All rights reserved

Copyright © 2014 by Yaron Reshef

[email protected]

www.facebook.com/288349054701616

Translation: Nina R. Davis and Shira E. Davis

Cover design: Lee Oshrat

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without prior written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book is dedicated to the memory of: my father, whose image I succeeded in reviving through this book; my mother, who passed away while this book was being written; my father’s friend Mordechai Liebman; my aunt Dr. Sima Finkelman; and the rest of my family members who perished in the Holocaust.

This book is dedicated to my family, so that they may pass the story on to future generations and keep these cherished memories alive.

Table of Contents

From Past to Present

The Lot, Part I

The Family, Part I

The Lot, Part II

The Family, Part II

The Family, Part III

Testimony

Memories

Viktor

On My Way

At the Archives

On Route to Chortkow

Chortkow

The Treasure

Kaddish

The Myth

Epilogue

About Writing

Family members:

Acknowledgements

From Past to Present

I am certain that I never invited the past to walk into my life. Not that I didn’t take an interest in our family’s history. On the contrary – in my youth, as well as in later years, I did try to trace my family’s roots and its history. Unlike my sister, who showed no interest in such matters, I eagerly absorbed any information relevant to my family. But no, I did not invite the ghosts of people long gone, nor the memories or emotions attached to them, to come visit me in Israel of 2012. It was as if some hidden hand orchestrated the perfect plot to pull me into the cauldron of family affairs.

It was as if this plot was produced especially in order to motivate me to embark on a year-and-a-half’s worth of obsessive searching for long-lost details covered in the dust of history, memories erased by generations of silence. As if the invisible entity directing the action knew me intimately and knew full well that I could not rest when confronted with an open case, especially a mystery involving my relatives both near and far, and a considerable amount of money. So perhaps it was chance or fate that colluded to pull the strings of quite a number of people and circumstances, who jointly presented me with an impossible riddle. It was the ultimate tool to create an emotional trap that would not let me push the subject aside, not even for a single day.

If you were to ask me what would be the best way to evoke in me the strongest motivation to explore the saga of my parents’ emigration to Israel and the fate of their families, I could not have come up with a more perfect puzzle; an attraction so aggressive in its pull as Life has presented me, in the form of a chain of chance events, during the past two years.

***

The Lot, Part I

I had no intention of writing a book. I had no need to write a story in general nor a story about my family and the Holocaust in particular. But life being what it is, sometimes things happen in mysterious, even surprising ways. Stuff that used to take center stage moves to the background, and background stuff moves downstage and center. That’s what happened in my case.

I began putting things down in writing because people close to me – family, friends, colleagues – told me repeatedly that I simply must write the story of “finding the lot” – a plot of land purchased by my father in 1935 and discovered seventy-seven years later.

The story begins in early July 2011, while I was in the US for work. My wife, Raya, received an unexpected phone call. The caller wished to speak to Yaron, son of Shlomo Zvi Finkelman. The speaker was attorney-at-law Elinor Kroitoru, head of Location & Information at Hashava, The Company for Location and Restitution of Holocaust Victims’ Assets. After introducing herself, Elinor asked Raya whether she had any information about a lot owned by my father in the country’s north. Raya said that she knows my parents came from Poland, but knew nothing of a lot or any other property they may have owned there. Raya naturally assumed that Elinor’s question had to do with property during the Holocaust, ergo in Poland, never suspecting that the lot in question was in Israel. At Raya’s suggestion, Elinor contacted my sister Ilana, who said she knew nothing of a lot owned by my father in Israel. Elinor told her that her office had located a lot near Haifa, purchased in 1935 by one Shlomo Zvi Finkelman who lived in Haifa, and that she was trying to trace that person or his beneficiaries. Apparently, her office was quite surprised to find, among the lands purchased by Jews who perished in the Holocaust, one bought by a resident of Haifa. Elinor was asking for my father’s address in 1935, hoping to connect between the buyer, whose address appears on the bill of sale, and our father. My sister replied that our father had lived at several addresses in Haifa after reaching Mandatory Palestine in 1932, among them Massada, Nordau, Hillel and Achad Ha’am streets. Elinor wanted to know the house numbers, of which my sister knew only two – 6 Nordau and 4 Achad Ha’am. Ilana suggested that as soon as I got back from the States I’d contact Elinor, because I may have further details.

A week later, when I got home, Raya told me about this unexpected phone call and how she had thought it was about a lot in Poland. “Talk to your sister,” she urged, “she’ll probably have much to tell you.” Ilana mainly repeated the story, adding that, meanwhile, she received a letter from Elinor recommending that we contact the office of the Custodian General at the Ministry of Justice to find out whether we had a legal right to the property in question. “You need to find proof that the Shlomo Zvi Finkelman appearing in the bill of sale is indeed your father,” said Elinor when I called her the next day. “I can’t help you any further, it's out of my hands. But it would help considerably if you knew exactly where your father lived in 1935, who this Mordechai Liebman guy was, and what was his connection to your father.” I was quite surprised at that, since I didn’t understand how a Mordechai Liebman fit into the story.

My father died in 1958, when I was seven. Any memories I have of him are vague -- mostly a few images of going fishing together, when I joined him and his friends on the navy pier at Haifa Port. These pictures are engraved in my memory, thanks to the joint experience and because of a small but impressive number of fishing successes, attributed by my dad and his friends to beginners’ luck. I also have some mental images of his work as a philatelist: hosting an American stamp merchant named Fogel in our living room, or sitting for hours sorting his stamps and trying to clean or fix damaged stamp perforations. I don’t remember spending “quality time” with my dad, or any father-son talks. For all I know, I may have erased memories through years of suppression. His sudden death from a heart attack one winter night weighed heavily on me for years.

On the other hand, I knew quite a lot about him, because my “aunts” (all relatives other than the immediate family were typically called “aunt” and “uncle”, as Polish Jews do), after the first affectionate cheek-pinching, would exclaim: “Gosh, the little one looks just like Junio!” My father, being the youngest child, was nicknamed Junio, probably the Polish version of Junior. Then they’d continue with tidbits of information about my dad’s personality, or some other family-related lore. I assume I collected these crumbs and stored them in my memory.

I suppose storing information in one’s memory is easier than retrieving it when neede

d. But sometimes, when I have to recall things relating to my family history, I’m awed at the stuff that suddenly pops up, not quite sure whether these are true memories or the product of my imagination. Only after receiving proof or external corroboration am I convinced that it was true memory, actual knowledge. Therefore, I was not wholly surprised when I heard myself answering automatically: “Mordechai Liebman was a good friend of my father’s in his home town, Chortkow; I think he perished in the Holocaust…”

“If you can find proof of that, it’ll help when you have to provide the Custodian General with information and documentation,” said Elinor.

So it came to pass that, in one day, my life took on a new focus: my father’s lot, and with it the questions: Who is Mordechai Liebman? What was his connection to my father? What was his connection to the lot? And where did that kneejerk response to Elinor’s question come from? I had some very vague childhood memories of tales of a lost lot, fragments of memories that must have come from two separate stories. The first was about a lot on Mt. Carmel that my father purchased. For some reason the name Shoshanat HaCarmel (literally “Rose of Carmel”) stuck in my mind. The story was that my father bought the lot from a local crook who conned him, and my family never actually received ownership. The other lot-related story is even more complex. In my childhood, years after my father’s death, while rummaging through forbidden cupboards, I came across drawings of what looked like an industrial building. Obviously, identifying it as an industrial structure came years later, when I learned to differentiate between types of buildings. To this day I clearly remember the drawing: flat, featureless façades, a perfect rectangular block with a saw-tooth roof; a sequence of right-angle triangles. Later, I learned at the Bezalel Academy of Arts & Design that this type of roof was very common in industrial and commercial buildings in the 1930s and ‘40s, meant to let in northern light while blocking direct sunlight. I vaguely remember a conversation with my mother, after she caught me snooping in the cupboard and looking at the drawings. “This was Daddy’s dream,” she said, “They wanted to build a kind of textile factory, similar to the ones in Poland… but it didn’t work out because of the pogroms…” I recall that she referred to the location as Yishuv Haroshet (literally: industrial settlement) or Mif’al Haroshet (literally: industrial plant). “They bought the place from a rabbi who was a swindler who then disappeared.” I know it sounds a bit strange that both snippets of memory have to do with lots and crooks, but my memory could have played tricks on me, mixing up the facts of the two tales. As for Mordechai Liebman, I knew nothing except that I once heard that he was a friend of my father’s, or at least that’s what I thought.

Regarding my father’s various addresses when he first came to Palestine, and my parents’ later addresses as a married couple, I had only fragmented clues that did not add up to a clear picture. Though my mother was a hundred and one at this point, she hadn’t been communicative for several years.

During the days that followed I began to get used to the idea that I was facing a new kind of challenge. According to Elinor’s instructions, I was to formally apply to Ms Hanni Amor, head of the National Unit for Location and Management of Property, at the Custodian General’s Bureau of the Ministry of Justice, attaching Elinor’s letter and asking them to handle the matter. And so I did: in mid-August 2011 I applied to receive ownership of a lot which, a month earlier, I didn’t even know existed.

Smiling, Raya said decisively: “This is a message from your Dad.” “Okay,” I replied, “but why now? Don’t you think it’s just a tad late, after fifty four years?” This was no innocent message; it handed me quite a challenge seeking information when there’s no longer anyone to consult or interview. That generation is long gone, and even my mother, alive at the time, was not fit to communicate and provide information. No way of knowing exactly what I was getting myself into…

I decided to phone Hanni Amor, and was surprised when she explained to me, politely and patiently, that she couldn’t help me. “It is up to you to find proof that your father is the Shlomo Zvi Finkelman, who bought the lot. Unfortunately I cannot help you or give you any info about the lot and its location. You have to provide my office with proof of your father’s residence in 1935 and his connection to Mordechai Liebman.” By the end of that exchange I felt I’d reached a dead end. It seemed like a puzzle wherein I’m expected to join two pieces that didn’t fit and place them precisely at an unknown address on an imaginary game board. Sounds surreal, right? That’s just how it felt.

For the first few days I was at a loss, had no idea where to begin. I searched for the smallest lead that would point me to the missing facts, but couldn’t come up with any creative idea. I tried to put myself in my father’s shoes, tried to imagine what he did upon arriving in Palestine, what trail he left which would help me track down his address. The second task was even more complex. Intuitively, I began with the basics: Who are you, Mordechai Liebman, and what was your connection to my father and the lot? Reason told me that Liebman’s name appears on the bill of sale as my father’s partner. I tried to visualize a situation wherein my father purchased the lot with a friend, perhaps to bring to life a shared dream, or simply in order to split the cost. This theory agreed with the facts as I knew them: My father first came to Palestine in December 1932, then returned to Poland in July 1934 to marry my mother, Malia née Kramer, whom he brought back to Palestine with him three months later, in October of that year. Had my father gone abroad with the purchase documents and recruited his friend as co-buyer? I couldn’t know for sure, but it sounded plausible.

Or perhaps my father had made Liebman’s acquaintance in Palestine, and they’d bought the lot together. But after careful consideration I discarded that possibility. Logic said that the only reason Hashava, the company engaged in locating Holocaust victims’ assets, would contact me about the lot was if one of the lot owners had perished in the Holocaust. Since Father lived in Palestine during the years in question, and also died there, then obviously his partner – apparently Mordechai Liebman – died in the Holocaust. Based on this speculative premise, I embarked on my search for Mordechai Liebman.

I began my quest with Yad Vashem archives. I searched for pages of testimony under the name Mordechai Liebman from Chortkow, my parents’ home town in Poland, currently in the Ukraine. Nothing. I searched for testimonials about Holocaust victims from the Liebman family in Chortkow and found nine testimonials, none of which had any mention of Mordechai. Most of the testimonials were from the early ‘50s, and I assumed it would be impossible to locate the persons in question; the addresses were old, and the people probably long dead. Having found nothing in the Yad Vashem archives, I began searching the Internet.

My parents on board the Carnaro, on their way to Palestine, 1934

The Italian passenger ship Carnaro

No sooner had I typed into Google (in Hebrew) the key words Mordechai, Liebman, Chortkow, than I apparently found Mordechai, right there in the second link displayed, which was “Meiselman, Getter, Cheled, Arbel, David – Chortkow.” That was a total surprise. I knew the Meiselmans, who later Hebraicized their name to Cheled. Asher Meiselman Cheled was a close friend of my parents’. As a child, after Father’s death, I spent many school vacations at their place in Yad Eliyahu in south-Tel Aviv. Their younger daughter, Varda, was my age; she taught me to fly little kites made of paper and tied with thread. You could say it was similar to origami, long before that concept made it to Israel. Tel Avivians called this type of kite “kifka”. In my home town of Haifa the kites were made of reeds and called by the name “tyara”. Within minutes I realized that the web page I landed on was set up by Miri Gershoni, to commemorate the Jewish community of Chortkow.

The page showed family photos from Asher Meiselman’s albums: his parents and his brother; my father as the head of Betar youth movement in Chortkow, surrounded by his girl troop who were members in the movement; and a photo of my parents and my sister Ilana, with Asher himself s

tanding next to them in his British soldier’s uniform.

But the real surprise was finding the photo of Mordechai Liebman. The bigger picture was beginning to emerge.

Mordechai Liebman, 1930

They were friends, apparently; Betar troop members and my father their leader. I knew that my father was older than the Meiselman brothers: Asher was six years younger, Shmuel – five, and the other brothers even younger.

My father as Betar Leader in Chortkow, 1928

When I was a child Asher told me that, when my father left for Vienna to study architecture and building engineering, it was he – Asher – who replaced him as Betar leader. Though the photo of Mordechai next to my father and the Meiselman brothers attested to the latter’s friendship, it was not sufficient proof of the connection between Mordechai and my father. I had to provide a document or some other evidence of their relationship. And so, unexpectedly, I had a photo of Mordechai from 1930, which I could look at to my heart’s content, but I still couldn’t talk to him, nor hear his version of the story of the lot.

So I continued to search memorial books and other Holocaust literature mentioning Chortkow, but in vain. No sign of Mordechai Liebman, save for the photo in my hand.

How am I to track down my father’s address in 1935? Where did he live after his arrival in Palestine in December 1932?

I had no knowledge about his first years in the country, so had no choice but to write down all I knew from family stories I’d heard in childhood, and from my mother’s memoirs as told to my sister and written down by her some 15 years ago.

My father’s address appeared on the love letters he sent to my mother, from Haifa to Chortkow. In these letters he described his search for work and the tension between the different Zionist movements, and the way he, as a young revisionist in “red” Haifa, felt discriminated against. But most of all, these letters were full of love and longing, and plans for their joint future in their new homeland. These letters, which I’d read as a youngster, were eventually lost. I still remember them on the shelf next to the bed in my mother’s bedroom, stashed in a carved wooden box made by my father, along with photos and postcards from family members who perished in the Holocaust. Years later, I arranged the photos in an album, but the letters themselves were gone.

Out of the Shoebox

Out of the Shoebox