- Home

- Yaron Reshef

Out of the Shoebox Page 5

Out of the Shoebox Read online

Page 5

I attached all relevant documents, properly validated and certified. A week later I called the office of the Custodian General to ensure that my declaration with all accompanying documents had arrived safely. “Processing takes around six months until a final decision is made,” I was told in response to my query. I didn’t have any doubt as to the nature of the final decision.

***

The Family, Part I

There would now be about a five-month wait until the Office of the Custodian General made a decision about the lot. I thought that after solving the puzzle I’d be able to clear my head and no longer be so consumed by the distant past. But I remained restless. I was amazed to discover how little I knew about my family. I did not blame myself for having taken no interest in it. I was annoyed at myself for not having made an effort to get more information while it was still available. It was only natural that I accepted my mother's short, evasive replies to my questions about her family in Poland. It was a painful and loaded topic for her all those years, entwined in immeasurable guilt – the guilt of a lucky survivor where others fell victim.

A few years ago, when my mother was ninety nine years old, she confessed that she never forgave herself for living while her whole family perished in the Holocaust. Again she told me the incredible events she shared with my father. How in 1939 they left Palestine for Poland with my sister Ilana, who was then a year old, to show off their eldest daughter to their parents. They arrived at Chortkow in Galicia on the eve of World War II as German forces advanced east using blitzkrieg tactics. Their parents, especially my mother's, did all they could to convince them to stay in Poland: "War is breaking out in Europe and it'll spread. Don't leave, it is much safer here, much safer than in Palestine..." quotes my mother. After long, intense arguments, my mother almost gave in, but my stubborn father insisted. They left Chortkow on the very day of the German invasion, their train under aerial attack. When they said goodbye to their families they never imagined it would be their last goodbye. "We could have at least saved Moshe, my little brother, I will never forgive myself for not saving him," my mother said seventy-one years later, with tears in eyes.

I felt a certain obligation to myself to try and peer through the veil of time and find out what happened to my family. I knew without a doubt that most had perished in the Holocaust, but for the first time I felt that the details also mattered. Perhaps my success in solving the mystery of my father's lot convinced me that it was still possible to delve into our history and create a picture more complete than the generic "perished in the Holocaust". What happened to my family in Chortkow after my parents left in 1939? "They were forced to dig holes and were shot... that's what we found out years later from witness accounts of those who survived that hell" – my mother told me time and again. When I persisted, my mother responded somewhat automatically "There were Aktions ...what does it matter? They were rounded up and murdered..." and the topic was closed. According to my simple calculations, at least three years had passed from the time my parents left for Palestine until their families’ deaths. What happened to them during that period? What were their thoughts? Their feelings? Did they know they’d been sentenced to death?

For the first time it bothered me that in a few years even the scant details I did know would fade and become part of the collective memory where nothing is personal. Holocaust memories will be unpleasant, an aesthetic blemish, but will no longer be painful. In order to feel pain one needs a personal connection to the victims. A connection that makes the historical chronicles part of your own personal narrative. I hoped that through my research I would find that connection.

In many ways the story of my family is the story of Chortkow, the town where my parents were born, where they were raised and their personalities molded.

The town of Chortkow lies in a beautiful valley along the banks of the Seret River in the Ukraine. The town was surrounded by forests, the biggest and most beautiful of which was the Black Forest. The first records to mention Chortkow date back to 1427. In that year Chortkowici, the lord of the village signed his name to a letter of surrender presented to King Władysław (Vladislav) Jaeiello of Poland, in which the Polish nobility accepted the King's rule. In 1522 the lord of the manor, Jerzy Czortkowski, was given permission by King Sigismund I the Old to found the town of Chortkow. In 1578 the town was sold to Sieniawski Yiglski who built the magnificent Chortkow Castle in order to fortify and defend the town. In 1616 the town was sold to a Polish nobleman, under whom it flourished. In 1630 Count Potocki built the large wooden Church of the Ascension. In the mid-17th century (1647-1648) there were many pogroms, known as the Khmelnytsky pogroms, following which the local Jews were exiled until 1704. In 1672 the Turks conquered this part of Poland and Chortkow became the seat of the local Ottoman Pasha. The 17th century was filled with wars and battles against the Turks and Tartars. Chortkow was ruined and burned, its castle had turned to rubble and its churches to ashes. After the Treaty of Karlowitz which ended the long war between Austria and the Ottoman Empire, Chortkow was given back to the Potockis. Count Potocki allowed Jews to return to the town and in 1721 granted them rights. The Jewish community flourished and a stone synagogue was built around the remains of the old wooden one. As a result of the partition of Poland, Chortkow became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In 1865 the Austro Hungarian Princess Hieronima Borkowska sold her palace in Chortkow to Rabbi David Moshe Friedman, known by the Jewish honorific as Admor, who made it his residence and the Hasidic center of Galicia. After the death of Rabbi Friedman in 1904 his son Yisroel Friedman took his place as the Hasidic leader, but moved to Vienna during World War I. Rabbi Friedman, also known as the Rabbi of Chortkow, always visited Chortkow for holidays and the city would fill with his followers who came from all over Galicia. This is the short history of Chortkow, where my parents were born.

I am the son of two families, Finkelman and Kramer, which represent the two cultural poles of the Jewish community in Chortkow, and likely Galicia.

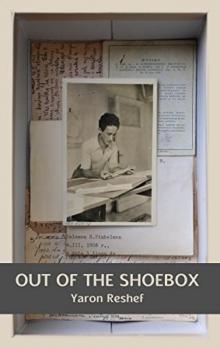

My father's family – the Finkelmans – was a well-to-do family of lumber merchants. Photos of my grandparents illustrate their typical central-European clothes and looks – an Austrian German sort of style. My grandfather Isak (Itzig) had a short beard and his payot (Jewish curly sideburns) were trimmed. The family sent their children to study in Vienna. Ethel, my father's eldest sister, mysteriously immigrated to the US and I do not have any further information about her. My Aunt Simka graduated from medical school. My Uncle Chaskel wanted to be an opera singer, but studied law instead due to parental pressure. As a student he was enamored with Zionist ideals and moved to Palestine in 1920, settled in Rosh Pina but later came down with malaria and left the country for good. My Aunt Zelda completed her PhD in philosophy and my father, Shlomo Zvi, graduated from architecture and construction studies. You can say the Finkelman family represented the Jewish Haskalah (“Enlightenment”) Movement.

Rivka and Isak “Itzig” Finkelman

In comparison, my mother's family, the Kramers, were a Hasidic family. My grandfather's face, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, was covered in a heavy black beard. His face, as well as my grandmother Fradel's, wore a soft expression compared with the harsh looks of my father's parents. My mother's parents were about twenty years younger than my father's. My mother was the eldest in her family, and my father the youngest son which is why he was called Junio, meaning junior.

Menachem Mendel and Fradel Kramer

The Kramer family came from a small village named Yazlovets near Buchach, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) west of Chortkow. I suppose my mother's grandparents moved to Chortkow after they got married and had children. They likely moved to town in order to find work and improve their quality of life. As a young couple they started their own business, were successful and became wealthy. My mother described her family and life at home in her memoirs:

"I was born in 1911 in Chortkow. It is a small town in Galicia in the Ternopil province. My parents were Menachem and Fradel née St

einweiss. Their parents were also born in Chortkow. They had four children. I was the eldest. My two brothers, Anshel and Moshe, were four and five years younger than me respectively. My sister Sarah, whom we called Selka, was the youngest and 8 years my junior. [My mother did not get their ages quite right: she was the eldest, then Anshel, Selka, and Moshe was the youngest].

Aside from us, there were three young orphans who lived with us – my father's youngest siblings. Their parents died in an epidemic so my parents took them in and raised them as they raised us. It bothered me quite a bit, I was jealous of them, which happens often among children. My parents were very careful in the way they treated my father's younger siblings and whenever we quarrelled they always took their side, and I took it to heart as though my parents were against me. The orphans were Malca, Nachman and Moshe. They were a bit older than me. My parents were very well off. They were wholesalers. We had a large three-story house. Downstairs was the store which had many rooms, probably five, and the staff. There was an accountant and another five workers. They were all Jewish. My parents chose employees from families that needed the income. They gave them a job at a young age and the employees stayed at their job for many years. Even my father's brother, Baruch, who was older than the orphans who lived with us, worked and lived in that house with us. Later he got married and left. It was a wholesale store, and the customers were haberdashers (selling thread, socks, underwear etc) with their own stores in our town and other towns in the area. My parents would buy the merchandise in factories in the big cities like Lodz. They acted as agents for the factories and would sell their wares in our region.

On the second floor, right above the shop, lived our family, and the third floor was rented out to two other families. We slept two to a room, one room for my parents, one for me and my sister, and one for my two brothers. Malca had her own room. Later, when I was about ten, she was married off, with a dowry as was customary back then. Her two brothers, the adopted orphans, shared a room as well.

Two young Christian maids also stayed in the house, as well as a Jewish cook. Father and mother both worked long hours at the store, so mother took on the Jewish cook so we could keep a kosher home. We also had a Jewish governess whose job it was to make sure that each morning we would pray and offer thanks (Modeh Ani prayer). She made sure we did our homework and didn't fight.

It was a brick house, with wood floors. The maids would polish the floor with a paste and special brushes they would wear like sandals on their feet. There were two bathtubs and several toilets. On the ground floor were a large dining room and a large kitchen. We always ate in the dining room and the servants ate in the kitchen. The kitchen had a large porcelain-tiled, wood-fired stove. We bought our bread at a kosher bakery, but always baked our challah for the Sabbath at home. On Friday they would send me to give out challah to the poor, and even when I was seeing Junio he would come along. We ate typical Jewish food at home: lokshen mit yoykh (noodle soup), with homemade noodles. We were never made to eat vegetables, and to this day I don't eat vegetables. Aspic (meat in gelatin), noodles with butter, perogies, stuffed fish, cholent (traditional Jewish stew) in the oven for the Sabbath etc. Food was prepared fresh every day. There was no fridge and food was stored in the basement. The house was located on Sobieskiego St and on the other side of the street, not too far away, was a bus station where you could get buses to nearby towns. We had electricity in town, and the house had electric lighting.

I stayed home until I was six. There were no kindergartens. When I was six I started going to a Polish school and in the afternoons I studied in a Hebrew Jewish school where we studied Hebrew, the Old Testament and Jewish history. The classes were all in Hebrew. At home we spoke Yiddish with our parents, Polish with the maids, and amongst ourselves mostly Polish. Our morning classes were four hours, as were the afternoon classes. I knew Hebrew as well as I knew Polish. We learned Hebrew in the same accent spoken in Israel. My parents knew the holy tongue with a thick Eastern European (“Ashkenazi”) accent but didn't use it regularly.

I graduated from the Polish high school, and wrote my Polish exit exams as I continued to study Hebrew. They were very strict in the Polish school. The teachers would rap our knuckles with a ruler if we were talking or otherwise disturbing the class. When we addressed the teacher we had to get up and say "Mr. Teacher". There were many punishments, like standing in the corner. The Hebrew school, in comparison, was pleasant and easy-going. Most of the students at the Polish school were Christian. Tuition was high and you had to pass a lot of exams in order to be accepted. I had Jewish friends in every class. Jews did not make friends with the Christians, who were anti-Semites. Despite that, they rarely bothered us. Classes were not co-ed, they had either boys or girls. In the Hebrew school the classes were co-ed. They weren't strict there, so we all went there willingly even though it also had exams and report cards. This was the only Hebrew school in the whole region. All the children who lived at our house went to both schools, the Polish and the Hebrew."

I knew much less about my father's family. My mother never told me anything, and I didn’t ask. My only source of information was my Aunt Zelda. Zelda Finkelman, Liebling after she married Joel. She was often around at my father's home. Zelda's grandfather, Mechel, and my grandfather Itzig were brothers. When Zelda's father died in 1921 when she was only three, she and her mother and sisters moved in with my grandfather at 279 Szpitalna St. Zelda and her husband Joel were among the few who survived the Holocaust.

Zelda's sister, Zanka, was my mother's classmate and she was the one who introduced them. "... Come with me to Betar, it will be a chance to be around Junio... it's the best way to get to know him without anyone being the wiser..." my mother told me. Even after my grandfather died in 1933 Zelda stayed with them. From Zelda I learned how strict and unyielding my grandparents were: "The Finkelmans were always very stubborn, they never let anything go – not in business and not in their personal life at home..." The Finkelmans were Zionists. My Uncle Chaskel who studied law joined a group of immigrants that was known as the Student Aliya and immigrated to Palestine in 1920. After he came down with malaria he returned to Chortkow, got married and immigrated to Colombia inspired by stories of South America and Colombia from a fellow Zionist pioneer (halutz) who had travelled the world. My Aunt Simka was the girls’ coordinator in Hashomer during the early '20s. She immigrated to Palestine in 1935 and returned to Chortkow about a year later. Simka continued in her Zionist activism as the on-hand doctor for many youth group activities. My father, the youngest son, was a leader in Betar and lived up to the movement's vision by immigrating to Palestine in 1932. Zelda told me that their family originally came from the town of Jagielnica. Like all Finkelmans my grandfather and his family were lumber merchants. They were well-to-do which allowed them to provide all their children with higher education. Zelda told me that my father was the mischievous one. He was always athletic and played a lot of sports. One of her favorite stories was how he came downstairs one day all the way from the top floor walking on his hands. Apparently, my grandmother had never seen anyone walking on their hands before, let alone doing so on the stairs. She tried tilting her head to correct the upside-down image, and when she saw my father holding the stairs above his head she cried that he was possessed and fainted.

I first met Zelda as a teenager, when she visited Israel. I was immediately taken with her, and whenever I traveled to the States for work I would visit her if I could. She and Joel (Lolo) would always be happy to have me and provide me some more information about our family. And so we spent hours, as she helped me write down a detailed family tree, or told me with incredible candor about what she went through during the Holocaust. How she escaped the horrors, how she hid in a bunker and lost her family. Zelda let me read the diary she wrote during the months in hiding, and was happy to answer questions. I regret all the questions I didn't ask, and have no doubt that I missed a great opportunity to find out so much more about my family and life in Chortkow

as Zelda passed away in 1998 when she was only 80 years old.

One evening I sat down and summarized all the things I didn't know. This might seem odd as people usually sum up what they do know. But in this case I knew there was no one left who could provide answers and fill the gaps: Was my father's "capitalist" family forced out of their home after the Soviets occupation in 1939? They were, after all, lumber merchants and made their living from commerce. My mother never told me that her family was forced out of their beautiful house when the Soviets occupied the region. I only learned that from the address on the postcards that were sent from Chortkow to my parents in Palestine. The sender's address was now 10 Szkolna St. At first I didn’t understand the reason for the change of address. Only recently, as I looked deeper into the facts, I re-read my mother's memoirs and put two and two together. The sad story became clear, starting with the expropriation of their property and eviction from their grand house to the town's outskirts. On June 6th 1941 the German army entered Chortkow. Szkolna Street was within the boundaries of the Jewish ghetto that was created after the Germans arrived, so I suppose the family was not removed from their home again. I am certain that my parents knew what their family in Chortkow was suffering in these difficult years, at least until the German occupation.

Out of the Shoebox

Out of the Shoebox